Røysumtunet, a private clinic and not for profit institution founded in 1965 in Norway, is primarily known for providing care to patients with severe epilepsy.

However, in recent years, the institution has expanded to include patients with brain injuries, dementia, certain psychiatric conditions, and developmental disorders – and now, 12 single rooms are available for persons with severe or very severe ME/CFS.

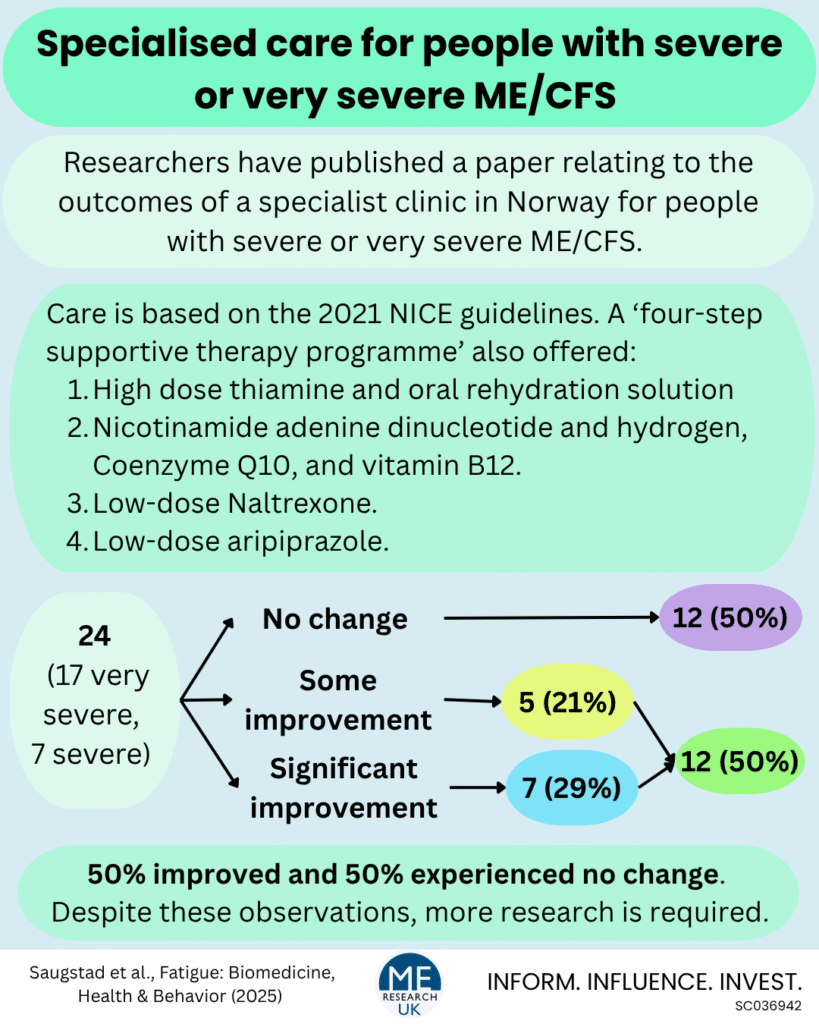

A team of researchers have published a paper assessing the effectiveness of the care provided at the clinic for people with severe or very severe ME/CFS.

About the clinic and care offered

The clinic’s values are centred around “equality, safety, coping, and well-being”, and services provided have been adapted specifically for people with ME/CFS, based on the information in the 2021 NICE guidelines, to provide individualised care.

This includes:

- Full assistance for those who are bedbound where needed.

- Access to tube feeding and intravenous nutrition as required.

- Facilitation of personalised activities.

- Support sessions ‘to help patients cope with ME/CFS’ held weekly.

- Admission to a single room with an ensuite bathroom.

- Adjustments to accommodate sensitivity to light and sound.

- An individualised care plan is developed and continually revised based on symptom severity and changing needs.

- Assistance for basic daily tasks, mobility, and use of aids according to their functional level.

- Social interactions – including interactions with health care staff – are adapted to the individuals symptom burden.

- Staff members also receive weekly supervision, as well as ongoing internal training and training for new employees.

Notably, all people with ME/CFS who attend the clinic do so on a voluntary basis, and family members are contacted according to preferences of the person with ME/CFS. Nurses, healthcare workers, and assistants work in round-the-clock shifts, with dietitians, physiotherapists, and psychologists available as required.

In addition to the individualised care plan, upon admission, each person with ME/CFS is offered a ‘four-step supportive therapy programme’ which consists of:

- High dose thiamine – also known as vitamin B1, which plays an essential role in energy metabolism alongside the proper function of the brain, heart, and nervous system – and admission of oral rehydration solution (1 litre given twice a week).

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide + hydrogen (NADH) and Coenzyme Q10 – both involved in cellular energy production, and vitamin B12 which is needed to make red blood cells to transport oxygen around the body, and ensures the normal functioning of the nervous system.

- Low-dose Naltrexone (LDN) – Naltrexone is a drug used to help alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder by reducing cravings and controlling physical dependence, at lower doses, it may reduce inflammation and improve immune response. Notably, although clinical trials are underway, there is insufficient evidence for this drug to be routinely prescribed for ME/CFS.

- Low-dose aripiprazole – aripiprazole is a medication prescribed for conditions such as schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, and at lower doses may be useful in the treatment of ME/CFS. However, as with LDN, much more research is needed to assess the safety and efficacy of this treatment in people with the ME/CFS.

In the paper it is stated that:

“The effect of each step is evaluated individually; if a step is deemed to contribute positively to the patient’s health, it is continued, and the next step is introduced: if not, it is discontinued. Consequently, after completing the evaluation of all four steps, a patient may end up utilising anywhere from one to all four steps concurrently”

Importantly, the authors of the paper note that this programme was developed based on clinical experience rather than robust research evidence, and more research is needed to assess the effectiveness.

What did the researchers do?

The team looked back on the medical records of 24 people – 20 women and 4 men – with severe or very severe ME/CFS, diagnosed using the Canadian Consensus Criteria, who attended the specialist clinic for at least 3 consecutive months.

The main outcome assessed was whether there had been a change in disease severity following treatment at the clinic compared to when ‘patients’ were admitted. A significant improvement was defined as a one level or more improvement in disease severity category (i.e. from severe to moderate ME/CFS, or from very severe to severe).

Disease severity was classified using the definitions from the 2021 NICE guidelines:

- Mild: “A person experiences approximately a 50% reduction in activity compared to before the onset of the illness”.

- Moderate: “Housebound for most of the time; the person may leave the house after careful planning”.

- Severe: “Bedridden for most of the day”

- Very severe: “Completely bedridden, requiring assistance for basic needs and deprivation from sensory inputs such as sound, light, smell, and touch”.

What did the results show?

In this study, 17 of the people with ME/CFS were very severely affected, and 7 were severely affected.

Over the course of the study, 7 people with ME/CFS (29%) showed a ‘significant improvement’:

- Three from very severe to severe.

- Two from very severe to moderate.

- Two from severe to moderate.

Symptoms for an additional 5 people with ME/CFS improved, but did not lead to a change in disease severity category: ‘These patients showed reduced fatigue, improved eating and nutrition, greater participation in personal hygiene, and/or an overall impression of general improvement’

Duration of disease, although not always known, was found to be associated with likelihood of improved disease severity; disease duration for those who improved during the study was shorter (2.3 years on average) compared with those who did not show improvement (an average of 6.7 years).

Importantly, although not all people with ME/CFS experienced an improvement in disease severity during their stay at the clinic, symptoms were not reported to worsen for anyone.

The paper did not report results relating directly to to the four-step supportive therapy programme.

Limitations of the study

- The research team stated, “we were not able to monitor and assess the patients as closely as we had anticipated”. This was due to the severity of disease, many ‘patients’ could not wear smart watchers and were only able to whisper a few words, some were unable to fill in self-report scales, even with help from clinic staff.

- It was also noted that a systematic overview of the potential effects of the supplements offered to those with ME/CFS was not possible.

- Only 24 people with ME/CFS were included in the study, this is a relatively small sample size and does not allow firm conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of the care offered at the clinic.

What do the findings mean?

Despite the small sample size, and limitations of the information collected, findings suggest that the care provided at the Røysumtunet clinic for people with severe and very severe ME/CFS is associated with an improvement in symptoms for approximately 50% of those who attend for at least 3 months, and that this improvement is equivalent to an upward change in NICE 2021 disease severity category for around 30%.

The care provided at the Røysumtunet clinic was based largely on the recommendations made in the 2021 NICE guidelines, except for the four-step supportive therapy programme. Research in large and diverse groups of participants is needed to assess whether the care alone is enough to lead to an improvement in ME/CFS symptoms in those with severe and very severe forms of the disease, or whether the improvements observed were due to either the therapy programme alone, or therapy programme combined with care. If the latter, the safety and efficacy of the programme should be assessed.