Considering that many of the conversations about postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) focus on blood pooling in the lower limbs and interventions like fluids and compression garments, it’s understandable that people often assume low blood pressure is a key feature of PoTS. However, this isn’t necessarily true. In fact, people with PoTS typically have a normal or even elevated blood pressure, especially when upright.

Let’s break down the name of the condition, as it gives us clues:

- Postural: Refers to the body’s position. In PoTS, symptoms are triggered or worsened by changes in posture.

- Orthostatic: Relates to being upright. So, sitting or standing up triggers PoTS symptoms.

- Tachycardia: This simply means a fast heart rate – the hallmark of PoTS .

- Syndrome: A collection of symptoms/signs that occur together.

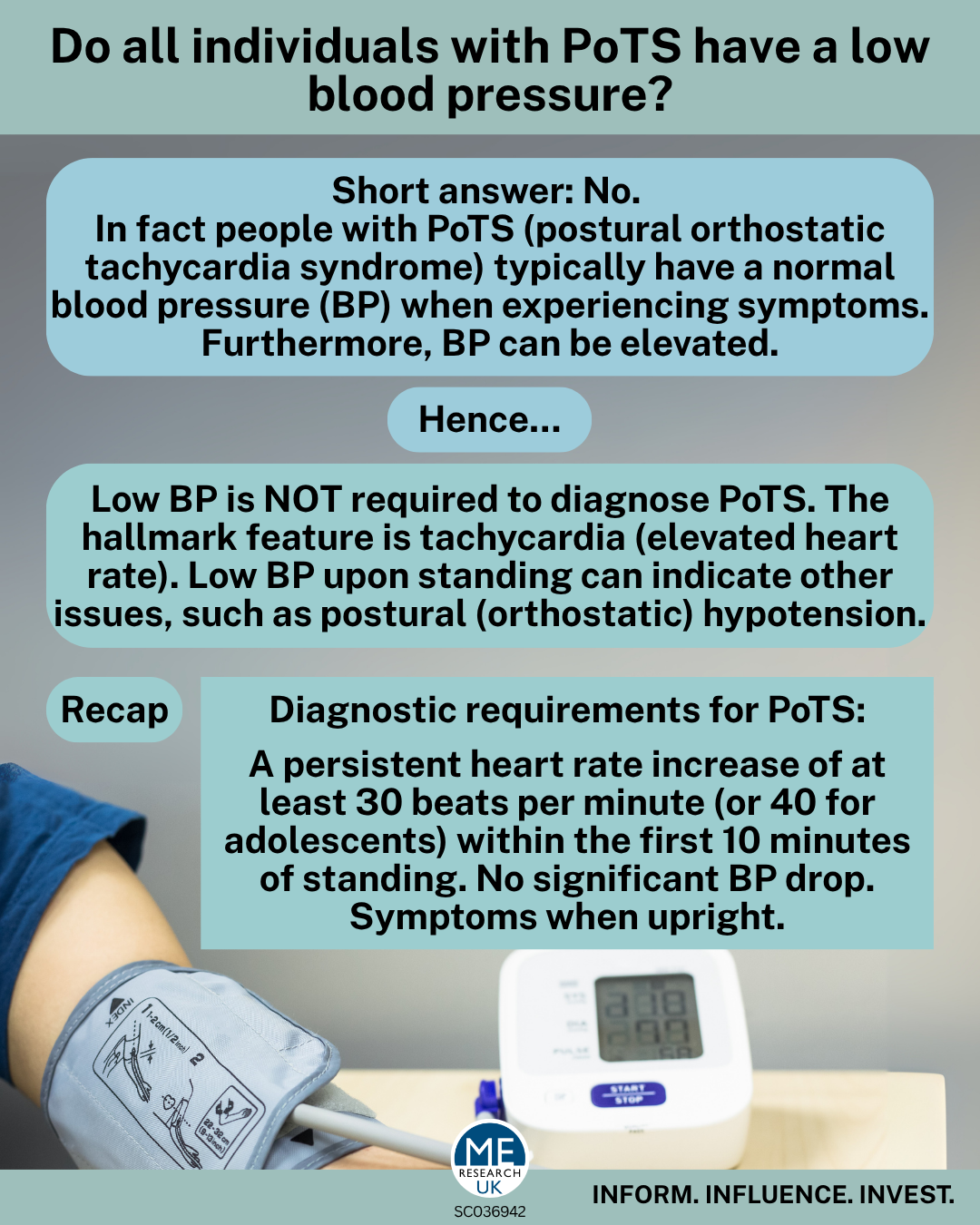

As the name indicates, the defining feature of PoTS is an abnormal increase in heart rate upon standing – not a drop in blood pressure. Nevertheless, people often experience symptoms like dizziness, lightheadedness or increased fatigue when upright, which can feel very similar to symptoms of low blood pressure (hypotension).

Key points

PoTS is defined by heart rate, not blood pressure.

The diagnostic criteria for PoTS include:

- A persistent rise in heart rate of ≥30 beats per minute (or ≥40 in adolescents) within 10 minutes of standing or during a tilt table test.

- No significant drop in blood pressure.

This means that you can absolutely have PoTS even if your blood pressure stays normal – or even increases – when in an upright position. In fact, if your blood pressure drops by a large amount, this might suggest another issue, such as orthostatic hypotension (otherwise known as postural hypotension).

But why doesn’t blood pressure drop?

When we stand up, gravity pulls blood down towards the legs and abdominal area. In a healthy person, the body quickly responds by tightening blood vessels (vasoconstriction) and slightly increasing heart rate. These adjustments help keep blood pressure and blood flow to the brain stable.

In PoTS, this response is thought to be dysregulated. Blood vessels don’t constrict efficiently, leading to pooling of blood in lower extremities. To maintain blood flow to vital organs, especially the brain, the body compensates by increasing heart rate and activating the sympathetic nervous system.

This compensation often seems to work just well enough to prevent a significant drop in blood pressure – but not necessarily well enough to fully preserve blood flow to the brain.

What does this mean?

This means that even though your blood pressure reading might look completely normal, your brain may not be getting quite enough oxygen-rich blood when you’re upright. This can result in symptoms like lightheadedness.

Some studies suggest that cerebral autoregulation – the brain’s way of maintaining stable blood flow even when blood pressure changes – is impaired in PoTS. So in PoTS, the brain may struggle to compensate for changes in blood pressure and thus struggle to get the blood it needs.

Potential reasons why certain interventions help

- Fluids and salt: Increasing fluid and salt intake boosts blood volume, which helps fill the blood vessels more effectively and supports overall circulation. This can reduce the need for extreme compensatory heart rate increases.

- Compression garments: These work by mechanically reducing (physically “squeezing”) blood pooling in the legs and abdomen. This helps more blood stay in the upper body.

- Elevating legs: This approach uses gravity to help keep blood from pooling in lower extremities.

- Beta blockers medications: In some cases, medications are used to limit excessive heart rate responses. This may be beneficial in hyperadrenergic PoTS.

These treatments don’t necessarily “fix” the underlying dysfunction, but they can support the body’s effort to maintain blood flow and reduce symptoms.

Conclusion

PoTS is defined by heart rate changes, not BP changes. What seems to be often happening is that the body is doing its best to compensate to an upright posture, but that compensation doesn’t always fully protect blood flow to the brain. This helps to explain why symptoms occur, even when blood pressure readings are “normal”.